In my last few posts I’ve laid some groundwork by explaining how to interpret NFP effectiveness rates, and then reviewed Marquette’s effectiveness rates for women in regular cycles. Now it’s time to talk about the breastfeeding transition. About 90% of my clients are breastfeeding when they start using the Marquette Method of NFP. Why? Because when you’re using NFP, everything changes when you’re breastfeeding. Quite often the symptoms of fertility that are normally tracked with NFP become confusing during the breastfeeding transition.

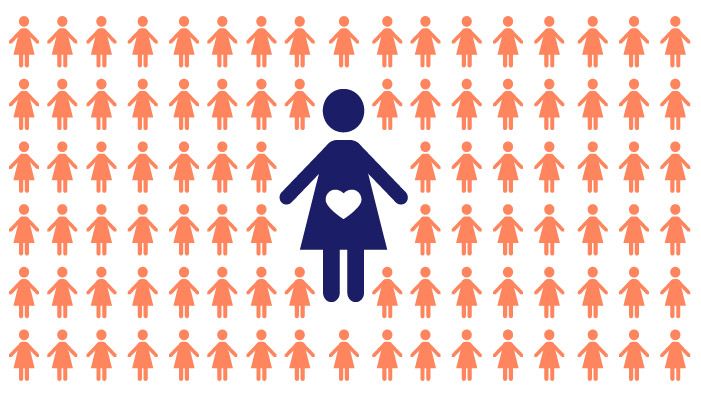

The breastfeeding transition can also be a challenging phase of fertility to navigate with NFP because there are so many uncertainties. Breastfeeding delays a woman’s return to fertility by 183 days on average. About 20% of breastfeeding women ovulate within the first 6 months of their baby’s birth, and 64% ovulate by 12 months postpartum (Tommaselli, Guida, Palomba, Barbato, & Nappi, 2000). Approximately 2/3 of women will ovulate before their first period after the birth of their baby, so it’s possible for a woman to become pregnant again without first experiencing a period.

That average number—183 days before the first period—hides an enormous amount of variability. Every woman’s experience of the breastfeeding transition is unique, and there is a very wide range of normal. Some women experience a very long stretch of infertility while breastfeeding. Others return to fertility relatively quickly after the birth of their baby, despite continuing to breastfeed. The range of normal goes from a couple months, to a couple years.

There is no way to predict, in advance, whether you’ll have a long or short stretch of infertility while breastfeeding. Because it’s possible for you to ovulate prior to experiencing your first postpartum period, it’s really important to track your fertility through the infertile time in the breastfeeding transition, so that you can pick up on your body’s signals indicating a return to fertility. Women who continue to breastfeed once their cycles return continue to have elevated prolactin levels, which makes delayed ovulation common in the first three to six postpartum cycles. This delayed ovulation can cause the first few postpartum cycles to be long and irregular. There is a wide variation of normal in the postpartum phase!

I teach the Marquette Method of NFP. Most of my clients begin using Marquette during the breastfeeding transition, and they usually stick with the Marquette Method even once they’ve weaned their baby. I’ve found that there are two main reasons why women are drawn to the Marquette Method during the breastfeeding transition—effectiveness and objectivity. This post focuses on Marquette’s efficacy research among breastfeeding women, to give a statistical explanation of why so many women switch to Marquette after having a baby. I’ll explain the objectiveness factor in a later post.

Table of Contents

Who Can Use Marquette’s Breastfeeding Protocol?

The Marquette Method breastfeeding protocols follow a woman through the entirety of her breastfeeding journey. You do not need to be exclusively breastfeeding to be eligible: You can use the breastfeeding protocols if you are breastfeeding at all, either directly from the breast, or by pumping.

Marquette divides the breastfeeding transition up into two parts. “Cycle zero” starts with the birth of your baby, and extends up until you begin your period. The second part of the breastfeeding transition, the breastfeeding return to cycles, begins when you start your first postpartum period, and extends to the first six cycles back after the birth of your baby, as long as you continue to breastfeed. At whatever point you completely stop breastfeeding, the breastfeeding protocols no longer apply, and you will transition to the regular cycle protocol.

How Effective is the Marquette Method’s Breastfeeding Protocol?

Soon after developing their regular cycles protocol, the researchers at the Marquette Institute for Natural Family Planning, recognizing that the breastfeeding transition was a challenging phase of fertility for many women, began developing a protocol specifically tailored to the breastfeeding transition. Because of all the uncertainties that surround fertility while women breastfeed, a system of NFP that relies on direct hormone monitoring during the breastfeeding transition (rather than tracking the body’s symptoms of hormonal shifts) was a very promising direction for NFP research. Marquette’s breastfeeding protocols, just like its regular cycles protocol, use the Clearblue fertility monitor to directly track a woman’s urinary hormone levels (estrogen and luteinizing hormone) throughout the breastfeeding transition.

Marquette’s 12-month efficacy study for their new breastfeeding protocol was published in 2013 (Bouchard, Fehring, & Schneider, 2013). This efficacy study followed 198 women who used Marquette’s “monitor-only” breastfeeding protocol over 12 months of use.[1]

What were the results?

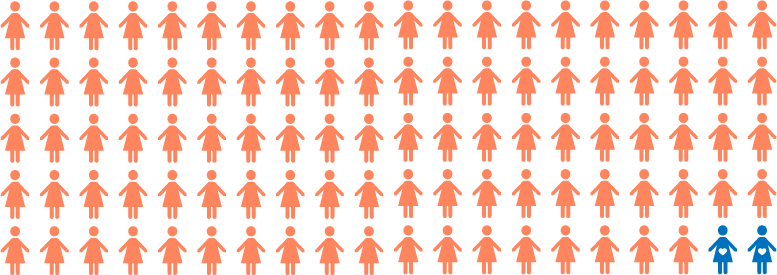

Marquette Method Perfect-Use Efficacy Rate—98%

The research showed that the protocol’s efficacy rate for avoiding pregnancy was 98% with perfect use. That means that 2% of the women experienced an unintended pregnancy over 12 months of using the method, even though they followed the method perfectly.

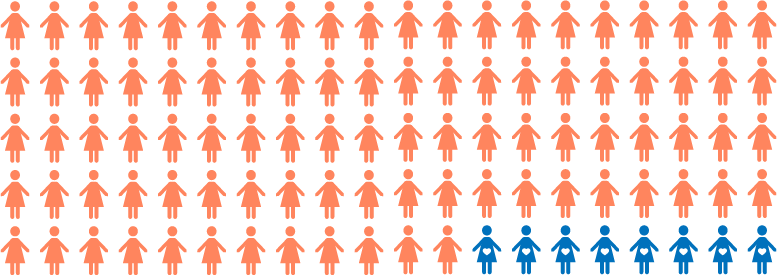

Marquette Method Typical-Use Efficacy Rate—92%

The typical-use efficacy rate was 92%, which means that 8% of the women in the entire study experienced an unintended pregnancy over 12 months of use. As a reminder, the typical-use rate includes all the pregnancies that occurred in the study. Pregnancies resulting from typical use include those that occur when couples, knowingly or unknowingly, deviate from the method instructions and become pregnant by engaging in intercourse on an identified fertile day. In short, it’s the measure of NFP’s effectiveness when it meets real life—and in this case, real life with a baby in the house.

That might seem like a wide variance (and it is, compared to the effectiveness rates for Marquette’s regular cycles protocol) but to put it in context, Marquette’s postpartum protocols are comparable to the effectiveness of the progestin-only birth control pill, which is 98% effective with perfect use and 93% effective with typical use (World Health Organization, 2018, p. 30).

When Did the Pregnancies Occur?

Couples often want to know how those efficacy rates break down. Is it more likely that the method will “fail” in cycle zero, or in the transitional cycles after fertility returns? It’s an important question for many couples.

Part of what makes this particular study interesting is that it provides some information about when the pregnancies occurred. Keep in mind this isn’t a statistical prediction, it’s just a summary of the experiences of a sample of women. Nonetheless, it’s interesting!

At the 6-month mark, none of the women in the study had an unexpected pregnancy. This means that the method was 100% effective, with perfect use and with typical use. This isn’t all that surprising—nearly all methods of NFP among breastfeeding women have perfect or near-perfect efficacy rates for the first 6 months, likely because breastfeeding delays the return to fertility by 183 days on average, which is … just over 6 months.

At the 12-month mark (at the end of the study) there were 8 pregnancies. Two of those were “perfect-use” pregnancies—the women became pregnant even though they had followed the method instructions perfectly. The first perfect-use method failure occurred at 9 months postpartum, while the woman was in cycle zero. The second perfect-use method failure occurred at 12 months postpartum, and the woman was in her third cycle postpartum when she conceived.

When did the typical-use pregnancies occur? Well, the researchers only reported specifically on the first one, which occurred in the seventh month postpartum. They did note, however, that most of the unintended typical-use pregnancies in the study occurred in the first few cycles back after the return to fertility, specifically in the first cycle after cycle zero.

The researchers speculated that this is probably because the first postpartum cycle is often longer than a regular cycle, with a delayed ovulation. This results in a long, frustrating stretch of abstinence which couples understandably find challenging.

One takeaway, if you’re planning to avoid pregnancy during the breastfeeding transition, is to know that the first few cycles after the birth of your baby might be longer than you want them to be—and that is normal. They might be frustrating to navigate—and that is normal, too. But if you need to avoid pregnancy, it’s so important to follow the instructions for the protocol, because these cycles can be very unpredictable!

Because of this research, I’ve structured my follow-up process to make the transition from cycle zero to postpartum cycle one as straightforward as possible for my clients. As soon as you peak in cycle zero, or as soon as you start your first postpartum period, I’ll schedule you in for a one-on-one teaching session so that the instructions for postpartum cycle one are fresh in your mind, right when it matters.

I’m a nurse, and I’m all about informed consent. While many women choose to practice Marquette while they are breastfeeding, I’d only want you to choose Marquette knowing what else is available. Each method of NFP has specific instructions for breastfeeding women to follow. And working closely with an instructor—whichever method you follow—enhances your chances of successful avoidance of pregnancy in the challenging postpartum phase.

The research that’s available on NFP use among postpartum, breastfeeding women has shown that the methods are all comparably effective in perfect use. Marquette’s 92% typical-use efficacy rate, however, does compare favorably with published typical-use efficacy rates for other NFP methods in the breastfeeding transition, which range 89% to 76% (Hatherley, 1985; Howard & Stanford, 1999; Perez, Labbok, Barker, & Gray, 1988). To compare Marquette to other methods of NFP, in terms of what fertile signs it tracks, visit my NFP methods comparison chart.

If you’re pregnant or breastfeeding and considering Marquette, I’d love to chat with you! I offer free consultations and can help you decide whether Marquette is going to be a good fit for you.

[1] Actually, 183 of the women in the study were breastfeeding, and 15 of the women were postpartum but not breastfeeding. In 2013, when this study was published, the protocols were used for both breastfeeding and nonbreastfeeding women.

References

Bouchard, T., Fehring, R. J., & Schneider, M. (2013). Efficacy of a new postpartum transition protocol for avoiding pregnancy. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 26(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2013.01.120126

Hatherley, L. I. (1985). Lactation and postpartum infertility: The use-effectiveness of natural family planning (NFP) after term pregnancy. Clinical Reproduction and Fertility, 3(4), 319–334.

Howard, M. P., & Stanford, J. B. (1999). Pregnancy probabilities during use of the Creighton Model Fertility Care System. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(5), 391–402.

Perez, A., Labbok, M., Barker, D., & Gray, R. (1988). Use-effectiveness of the ovulation method initiated during postpartum breastfeeding. Contraception, 38(5), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-7824(88)90154-0

Tommaselli, G. A., Guida, M., Palomba, S., Barbato, M., & Nappi, C. (2000). Using complete breastfeeding and lactational amenorrhoea as birth spacing methods. Contraception, 61(4), 253–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-7824(00)00101-3

World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research, & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP), Knowledge for Health Project. (2018). Family planning: A global handbook for providers (2018 update). Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/260156/1/9780999203705-eng.pdf?ua=1